Focal Scriptures Matthew 2:1-12 | Isaiah 60:1-6

Theme Connections

On Epiphany, we celebrate how God’s love transverses cultural and geographical barriers to become good news for all people. We marvel at the persistence of God to shine the way for the Magi so that they might bear witness to the divine. We honor that the Magi trusted their dreams and returned home by another way. As we journey forward, we carry the dreams of our ancestors in faith. With courage and resilience, we dream on.

I imagine they packed bags—

Water and food, blankets and clothes.

I imagine they packed tools—

Maps and telescopes that could bring the stars closer,

As if the sky was a comforter they could pull near.

I imagine they hugged loved ones and said,

“We’ll be back soon.”

And when loved ones said,

“Don’t leave,”

“It’s risky,”

“You don’t even know what you’re chasing,”

I imagine they put lips to foreheads and said,

“There is a light in the darkness. I must chase that.”

And then I imagine they walked.

I imagine they walked until legs were tired and knees gave out.

Maybe they told stories on the road and laughed into open sky,

Or maybe they sat in silence and prayed for more light.

However the road unfolded, I imagine it was not easy.

I imagine all of this, not because I’ve chased stars,

But because I have dreamed.

And these dreams for justice make the Magi’s story my own.

For every time we fight for justice,

We start in the dark.

We hug loved ones and say,

“There’s a light in the darkness, I must chase that.”

We walk until we’re tired,

And then we keep walking.

We laugh at the open sky as a form of resistance.

We pray in the night for signs of more light.

And no matter how important the journey is,

And no matter how much progress we make,

The journey to justice is never easy.

And so I pray,

That maybe one day,

We will be like the Magi,

And will walk ourselves into the light.

Until then, don’t forget—

There’s a light in the darkness. We must chase that.

Read Matthew 2:1-12

Commentary | Dr. Marcia Riggs

Alerted by a rising star that the “King of the Jews” has been born, three Wise Men wish to pay homage (v.1-2). According to the text, when King Herod hears about the birth, he and “all Jerusalem” with him are frightened (v.3). Herod seeks information about the birthplace of the child from the religious leaders, and then he reaches out to the Wise Men to inform him when they locate the child so that he too can pay homage (v.8). Two typical responses: Jesus will be recognized by some as God entering the world on behalf of all humankind; or Jesus will be feared as a threat to the rulers (political or religious) who exercise power over other humans.

The journey of the Wise Men discloses the power of a dream: “And having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they left for their own country by another road” (v.12). This is a dream of divine intervention. Although the Wise Men do not perceive Herod’s deception, it is known to God. Most importantly, though, they heed the message sent by God through a dream.

Womanist ethicist Barbara Holmes describes Creation in Genesis as “God busily untangling the chaos in the cosmos.” She describes God’s rest from creating thus: “The Holy One rests and perhaps dreams, then beckons us toward an unimagined future and the possibility of moral flourishing . . . . From now on, our lives will be nuanced and dependent on covenants and on our initiatives and commitments to God and others.”16

The imperative of Epiphany today is to receive all of God’s dreams: warnings, assurances, projections about how to persevere during this pandemic. The initiatives and commitments to God and others about how to flourish will surely come to us in our dreams.

16Holmes, Barbara A. Dreaming (Christian Exploration of Everyday Living). (Fortress Press, 2012). Kindle Edition, Loc. 603; 616.

Read Matthew 2:1-12

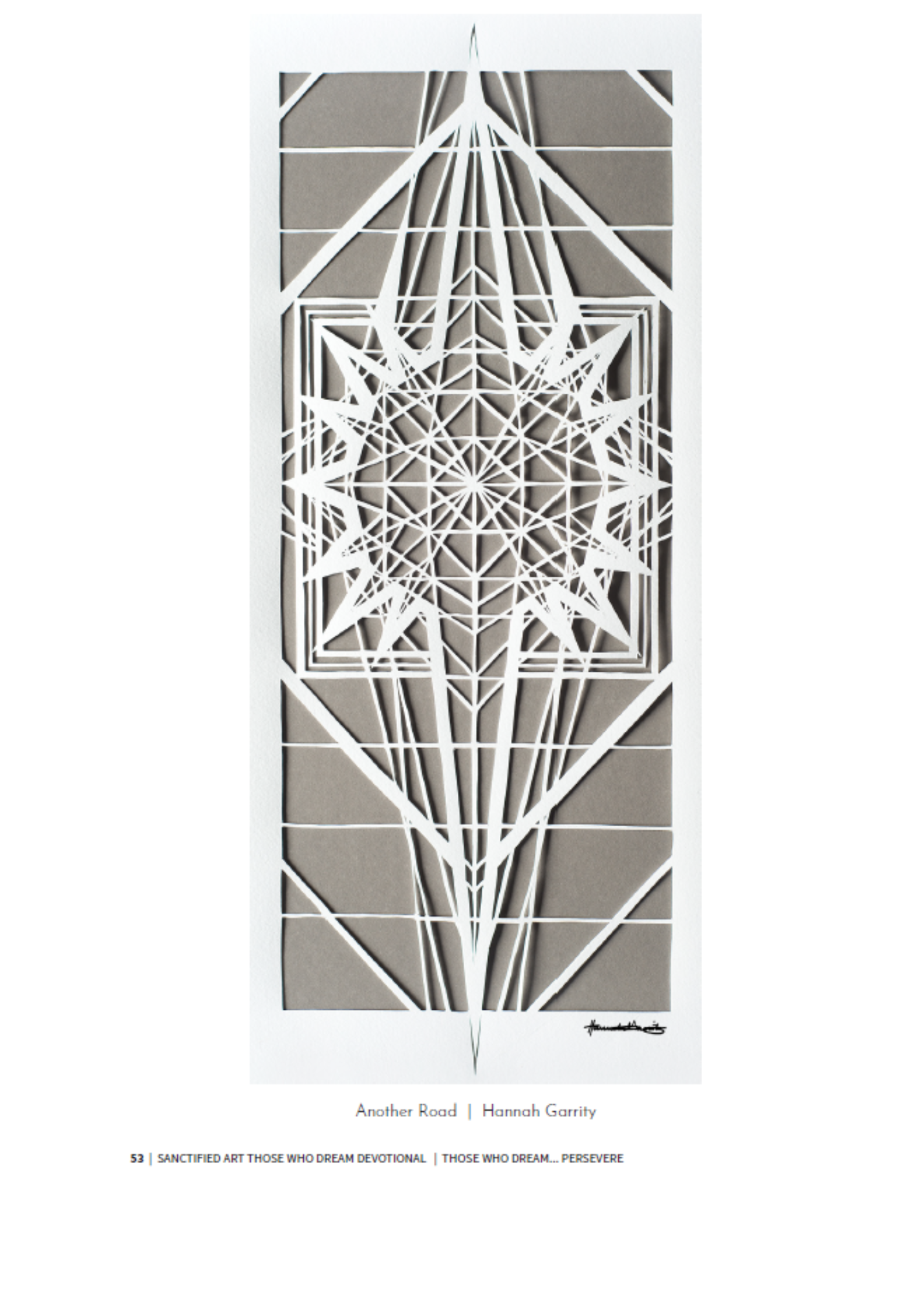

from the artist | Hannah Garrity

This image is a meditation on the gift boxes spiraling out from the center of the Star of Bethlehem. The top of the central square opens as Mary receives the gifts of the three Wise Men. Multiple paths surround the star, portraying the wise decision of the Magi to return home a different way to resist the fear-ridden power of King Herod.

“When King Herod heard this, he was frightened, and all Jerusalem with him.” The power of fear is palpable; it is easy for a leader to share and to use to his advantage. In this story we are reminded of the wisdom that has been gifted to us by God through Jesus’ ministry—the wisdom to avoid imbibing and stoking fear. Knowing this wisdom to be true, and knowing Herod to be a leader who leads fearfully and by fearmongering, I wonder how often we humans can fall into this pattern.

We know the story well. The Magi’s decision buys time for Mary and Joseph to make a move that will eventually save the life of God incarnate. They choose to leave the country as refugees, to escape the oppression that Herod’s fear imposes on their child.

Can we combat the fear within ourselves—to see beyond it to the love and hope that are also held in every moment? With each decision, we first choose our lens. Can we make it our intention to see the world through love, not through fear?

prayer

Breathe deeply as you gaze upon the image on the left. Imagine placing yourself in this scene. What do you see? How do you feel? Get quiet and still, offering a silent or spoken prayer to God.

Read Isaiah 60:1-6

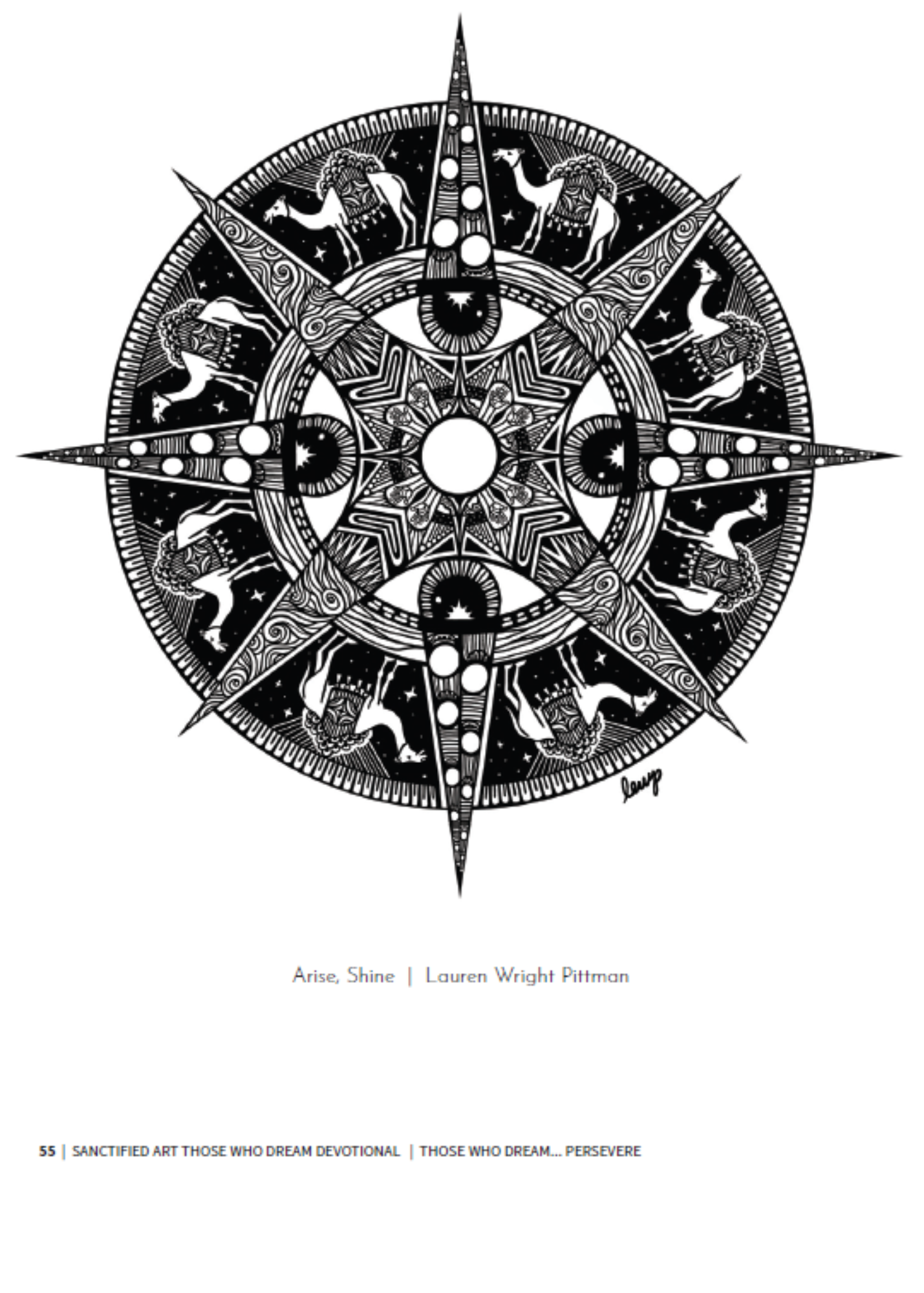

from the artist | Lauren Wright Pittman

As exiles returned home to Israel from Babylon, the prophetic words of this text would have been a glittering, hopeful, light-filled dream. This is precisely the kind of vision Israel would need to have a renewed sense of empowerment and a redefined goal for restoring Jerusalem.

This dream for Jerusalem is a complete overturning of what had become the norm in Israel’s troubled history. Instead of emptying their resources out in offering to overbearing empires, all nations would come to Jerusalem, bearing gifts, elevating Israel to a position of influence never before reached.17 This is the kind of overturning that fuels dreamers throughout the scriptures. For the oppressed, downtrodden, and cast-aside, God says, “Arise, shine; for your light has come.” These texts are filled to the brim with dreams to help us persevere on the path to realizing God’s dream for Creation.

I’ve been told that I’m naive because my hopes for the world are desperate and wildly unrealistic. I’ve been told that once I come of age, I’ll float back to earth and find footing in more grounded understandings of what is possible. To those people, I say: I will continue to set my vision on a horizon that feels impossible and will work toward justice, peace, and equity for all until my dying day. I pray that prophets continue to cast visions of glittering, hopeful, light-filled dreams which become our collective aim until heaven and earth meet.

prayer

In quiet contemplation, color in the page on the left, reflecting on how the imagery illuminates what you find in the scripture and artist’s statement. Conclude with a silent or spoken prayer to God.

17Brueggemann, Walter. Westminster Bible Companion; Isaiah 40-66, (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998), 205.

Take time to reflect on this past year, honoring its hardships and giving thanks for its gifts. In the space below, record all your dreams—big and small—for the year ahead.

All in All

Poem by Sarah Are

It takes strength to dream.

I imagine it’s that same strength that leads people to say,

“I love you” first,

Those three vulnerable words,

Wrapped in heart strings,

Whispered,

Because what could be

Is too good to keep quiet about.

It takes strength to choose joy.

It takes strength to push the covers

Off our weary bodies morning after morning,

To plant weary feet on solid ground,

And look for signs of beauty.

It takes strength to remember that we are not alone,

But the story starts with bone of bone and flesh of flesh.

That feels like so long ago.

Oh yes,

It takes strength to dream.

I imagine that’s why many choose not to,

For it would be far easier to simply sleep.

But there are always those who dream,

Those who are up at night picturing what could be,

Because this world is too good not to.

So we say, “I love you.”

We push the covers off.

We find solid ground.

We look for beauty.

And we dream.

We dare to dream.